Climate action in agriculture: can we expect much for the next decade?

The agricultural sector has so far largely benefitted from a free pass in the fight against climate change. Carbon dioxide emissions from burning fossil fuels have been seen as the main culprit driving the climate crisis, and that’s where most of the focus of climate policies has gone. Sources of greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture are more diffuse and complex, and have long been considered too difficult to tackle.

Yet, agriculture is a major driver of climate change. It is estimated that methane emissions have contributed 24% of the global warming effect to date. In the EU, agriculture is responsible for 54% of anthropogenic methane emissions. Globally, cropland soils have lost 20 to 60% of their pre-cultivation organic carbon content to the atmosphere, and in the EU, a tiny area of drained peatlands used for agriculture is responsible for 5% of our total greenhouse gas emissions.

So what is the EU doing to tackle agricultural emissions?

The answer is rather disappointing.

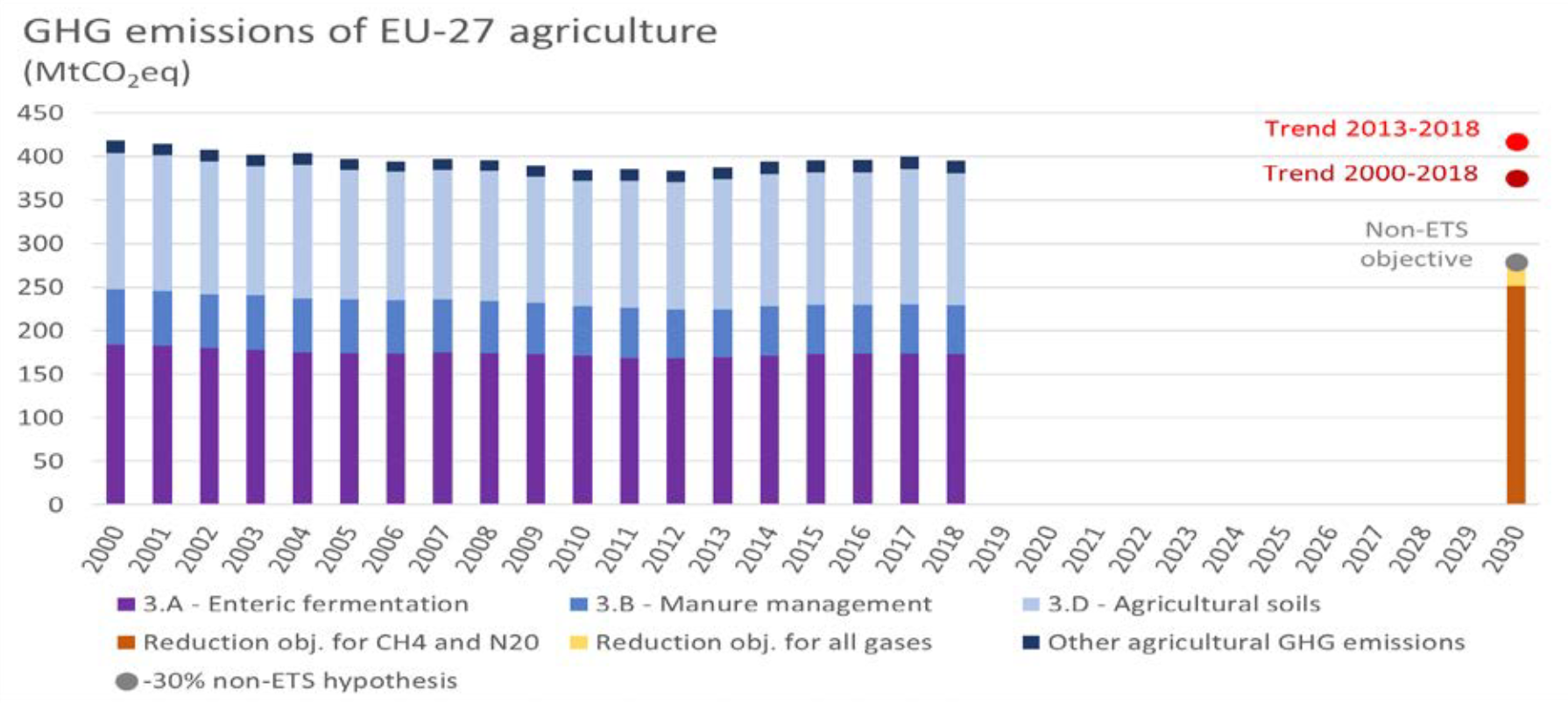

There is currently no specific reduction target for agricultural emissions. Agricultural non-CO2 emissions (from the use of fertilisers and livestock farming) are covered by the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR) alongside the waste, transport and residential sectors, allowing most countries to ignore agricultural emissions. Agricultural CO2 emissions (from farming on drained peatlands and poor management of grasslands or their conversion to cropland) are in the Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) sector, where emissions have been easily hidden by removals from forestry. As a consequence of this weak legislative framework, agricultural emissions have stagnated for the last 15 years, and EU governments are not projecting any significant reduction by 2030.

This partly explains the lack of attention given to the sector in the National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) highlighted by the PlanUp project. Planned measures in the agricultural sector are consistently the weakest part of the NECPs. Most countries rely on the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) for climate action in the farming sector. This is highly problematic, as the current CAP, which will stay in place until December 2022, has been found to have a negative or at best neutral impact on greenhouse gas emissions.

New CAP, new climate ambition?

The EU farming policy is currently under review. Experts and NGOs have warned that the new CAP threatens the EU’s ability to deliver on its Green Deal objectives. The EU’s pledge to halt biodiversity loss by 2030 is impossible without rapid, deep and large-scale changes to agricultural practices and landscapes. As to climate targets, reducing EU emissions by 55-60% by 2030 would be extremely difficult and expensive, if at all possible, if agricultural emissions stagnate or increase to 2030 as they are projected to.

So how is the post-2022 CAP falling short? Here are three key reasons why the EEB judges the new CAP, as amended by the EU governments and the European Parliament, to be a threat to the Green Deal’s climate objectives.

First, the CAP will continue to pay farmers even if they wreck crucial carbon sinks. Peatlands and grasslands are huge underground stores of carbon. Draining the former (peatlands are naturally wet) or ploughing up the latter causes major emissions. The European Commission had proposed rules to ensure their protection, which all farmers receiving CAP subsidies would have to respect. However, these rules were systematically watered down by MEPs and agriculture ministers. Taxpayers’ money will, therefore, continue to flow to farmers who are causing major, avoidable, CO2 emissions.

Second, the new CAP will most likely be business-as-usual for intensive livestock farming, which is responsible for the largest share of agricultural emissions (as well as water and air pollution). In early 2019, the European Parliament’s environment committee had adopted amendments which added strict safeguards preventing factory farms from getting CAP subsidies while ensuring support for nature-friendly livestock farms. However, in plenary, MEPs systematically voted those amendments down. For their part, member states never even discussed such safeguards.

This leads us to the third reason: the mirage of “eco-schemes”. Eco-schemes are an annual, hectare-based payment rewarding practices that are beneficial to the environment or climate. While it sounds good on paper, there are many reasons to fear that these new schemes will fail to deliver. First, eco-schemes cannot single-handedly deliver the far-reaching change that’s needed to tackle the multiple environmental crises agriculture is contributing to. With the bulk of the CAP geared towards business-as-usual, the €39-58bn earmarked for eco-schemes (in addition to €9-17bn for environment under Rural Development) out of the €273bn for 2023-2027, will struggle to make a big difference.

Furthermore, there is strong pressure from vested interest to ensure that those schemes are “easily accessible to all farmers” – meaning paying for current practices or only marginal improvements. The Parliament even adopted amendments proposing to use eco-schemes to pay farmers for absurd things such as using a mobile application that helps them manage their nutrients, maintaining some zones where they don’t spray pesticides, or complying with national laws. An MEP likened the situation to a “polluter gets paid principle”.

Much of the details depend on choices that will be made this year by national agriculture ministries when designing the so-called CAP Strategic Plans. Eco-schemes could still be a force for good. Subsidies could be used to help livestock farmers transition to nature- and climate-friendly models. Carbon sinks could be protected through national regulations. However, history tells us that when given flexibility in the CAP, EU countries systematically chose the least ambitious path.

But this could still change. Young climate activists recently got involved in the CAP campaign, and the massive public pressure calling on the Commission to #WithdrawTheCAP has had noticeable impacts. A continued mobilisation of civil society throughout 2021 will be crucial to help the Commission, progressive member states and MEPs salvage what can be salvaged in the upcoming negotiations and to ensure that national governments design ambitious CAP Strategic Plans. It will be an uphill battle, but one worth fighting.

Opportunities lying ahead?

Beyond the CAP, other policy initiatives are shaping up which have the potential to speed up climate action in agriculture. For example, DG CLIMA’s Carbon Farming Initiative, which aims at developing a certification scheme for carbon sequestration in agriculture. The project bears potential to unlock private funding streams for the direly needed adoption of sustainable land management practices, with climate and wider environmental benefits. However, it also carries risks which must be carefully addressed by the Commission. For example, this must not lead to carbon credits being used to compensate for emissions reductions in other sectors.

Another crucial development is the new climate regulatory framework, which could change the way agricultural emissions are addressed. This, again, presents both risks and opportunities. A weak framework could renew the agriculture sector’s free pass. But an effective framework, which should include legally binding EU and national emissions reduction targets for agriculture, could force member states to take action both in and outside of the CAP.

The EEB will engage closely with these processes in the new year. We hope you will too.

Contact: Célia Nyssens, Policy Officer for Agriculture